On Kiki Smith’s ‘Memory’ in Hydra in 2019 and other thoughts–

Bending time and space; like a border line, stretching it out so there is a large circular bend in the line and the straightness from before seems absurd.

In the opening pages of a book I bought reads ‘Greek identity is something that resides in our souls. It is not the borders but the culture and the spirit that defines Greece. Hydra is a special part of that identity … its tangible essence’ (Dakis Joannou).

Inside us all is this borderless intangible essence that is like a special spirit that can be summoned up; it is like a kind of memory; not that deep.

Do you remember why you are here? Do you remember how sunlight works? Do you remember what the colour blue means?

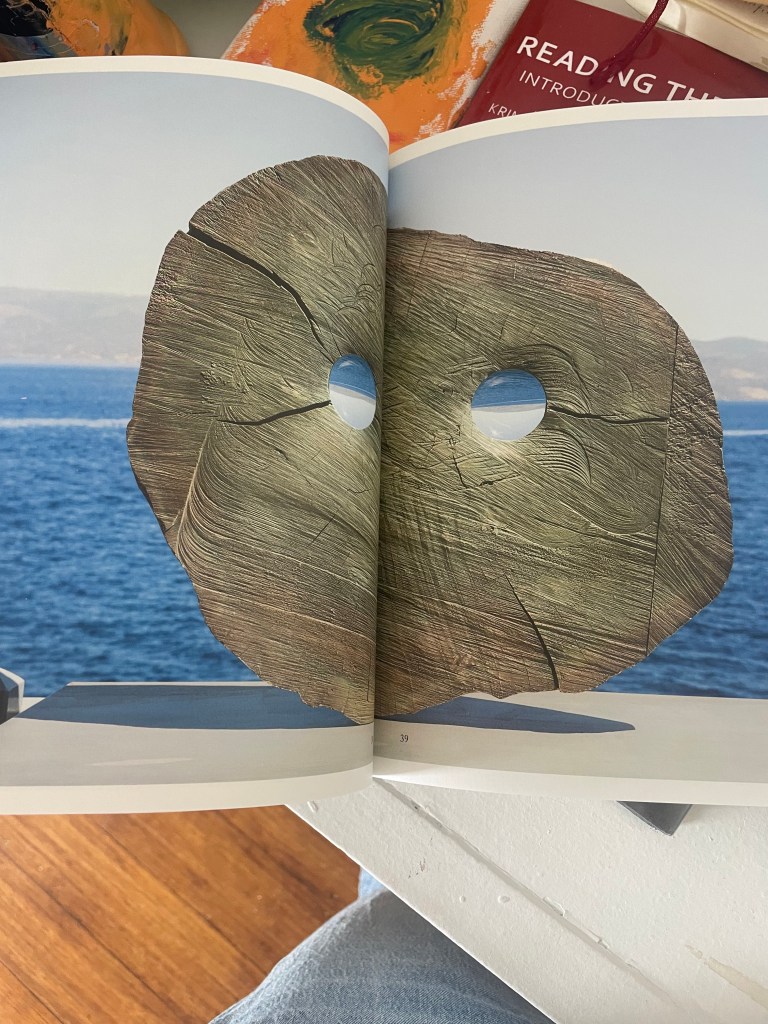

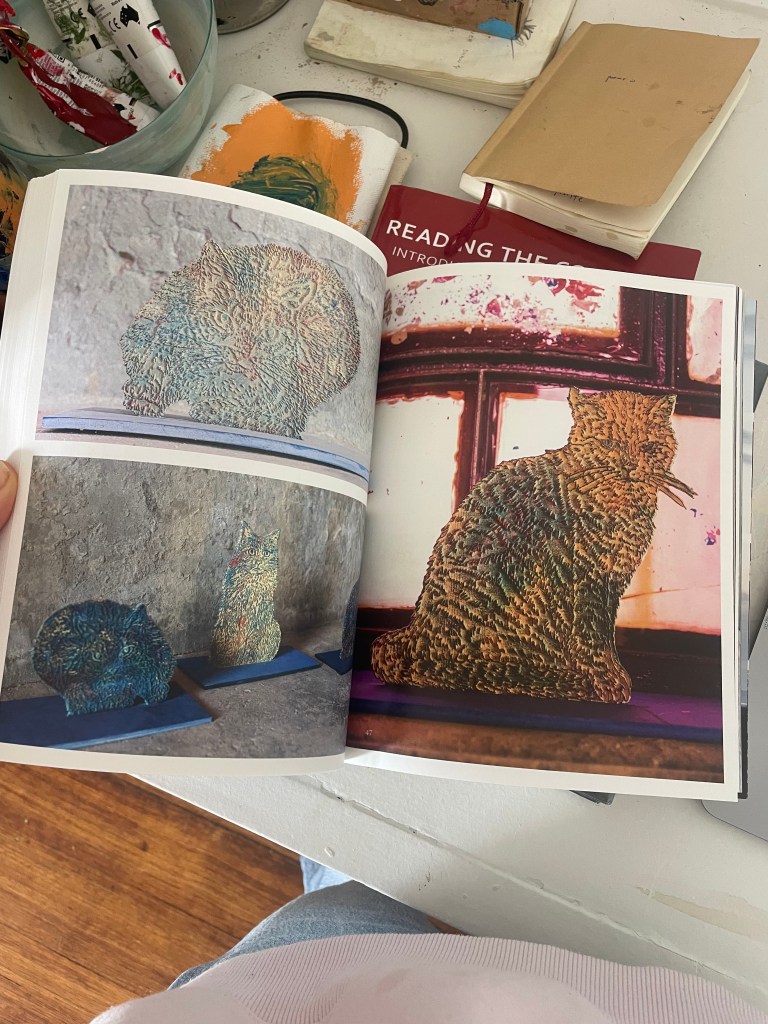

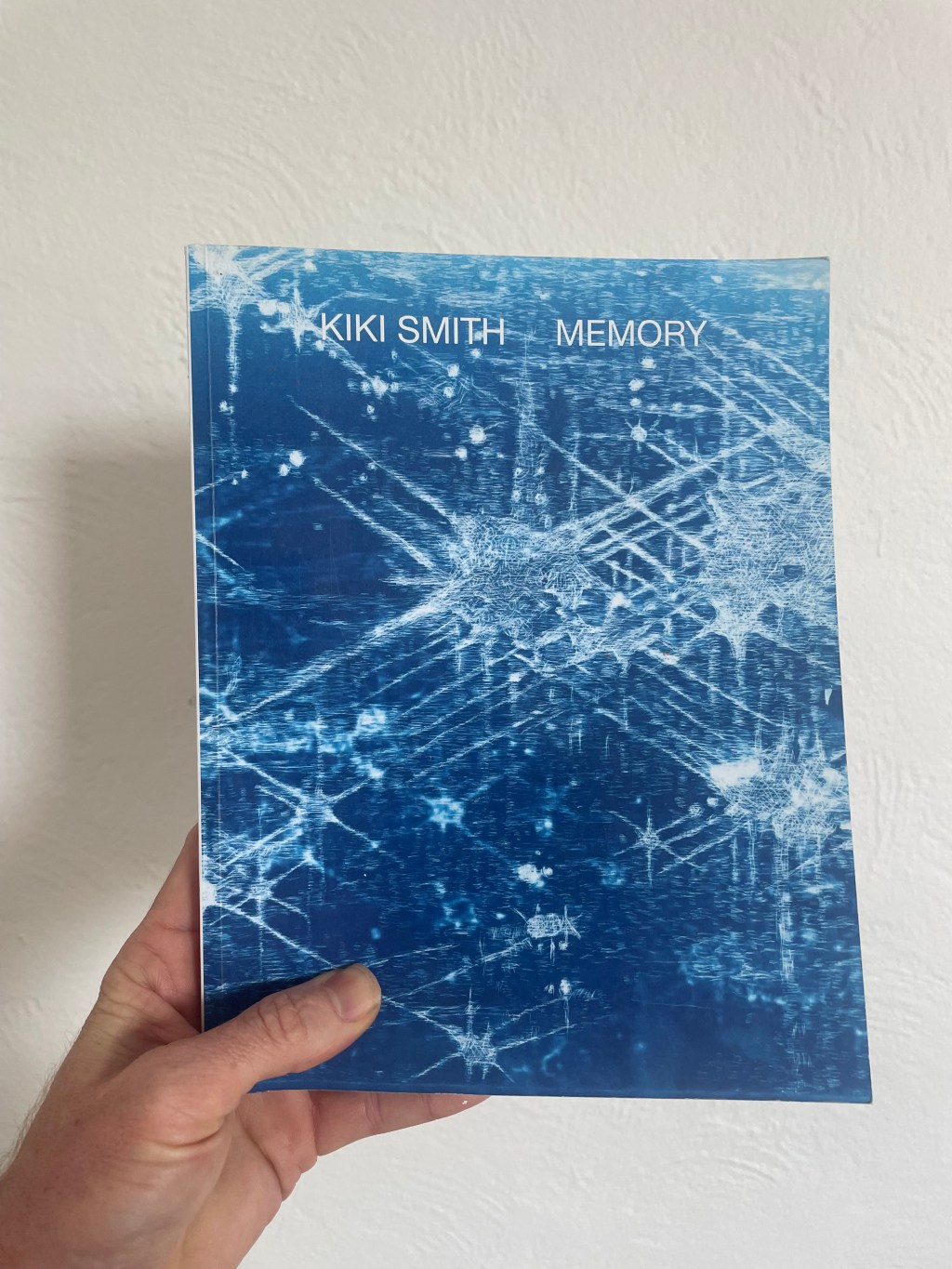

Memory is in infinite supply of questions that can provoke the artist to get to work or to remember again why they are working in the first place. For me I only have to look at the sea; see that it is still moving (beautifully) and still a shade of blue to remind me of the Aegean Sea, sitting on the rocks staring at that deep blue sea as a kid (I wasn’t a kid, but I felt like it). It was in Hydra a few years ago and that blue had a profound impact on me as did the stray cats, wildflowers, slow moving people and donkeys. And then I came across the book ‘Memory’ by Kiki Smith not that long ago who–a living American artist–was commissioned to make a show on site in the old Slaughterhouse by the Aegean Sea.

‘Smith combined various elements (both naturalistic and fantastic) into a multi-layered, multi-piece composition. An artist deeply attuned to the natural world and its symbolic manifestations, she unhesitatingly embraced the island’s rich menagerie of cats and donkeys, constellation creatures and mythological beasts, giving each a featured role in her almost theatrical tableau. The whole of Smith’s presentation can be seen as a coalescence of maritime history, mythology, astronomy, astrology, and site-specific anthropology; it speaks the the collective memory of a place, which, though relatively small, can be espied in the majestic and distant placement of stars’ (Maggie Wright, p.49).

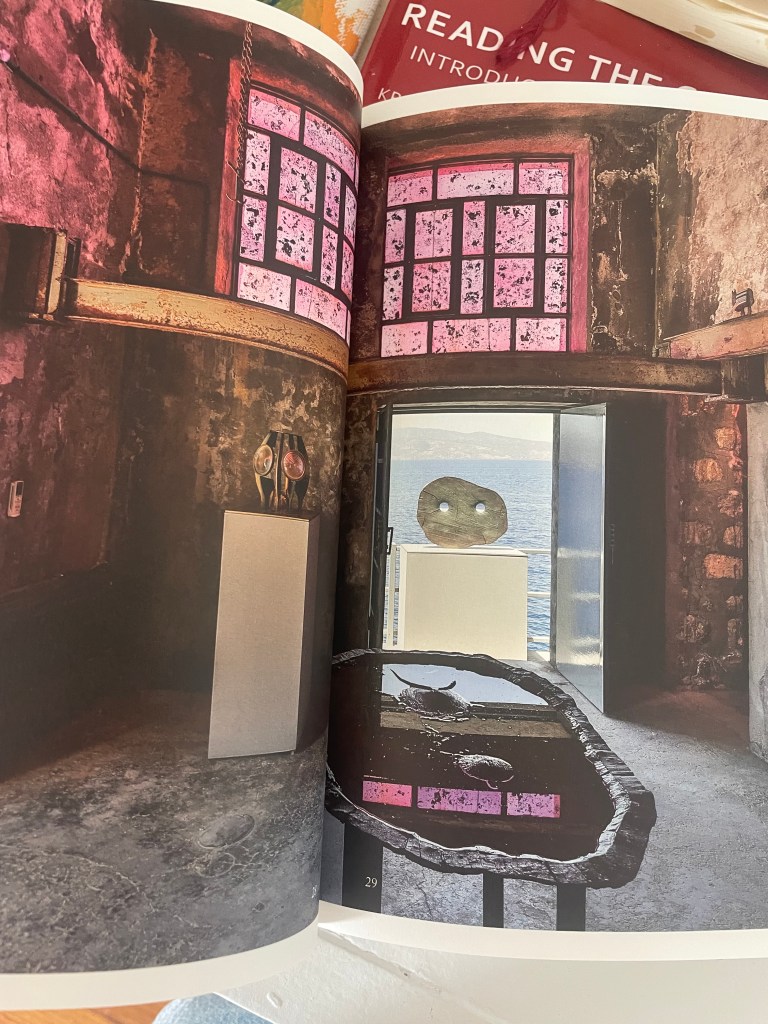

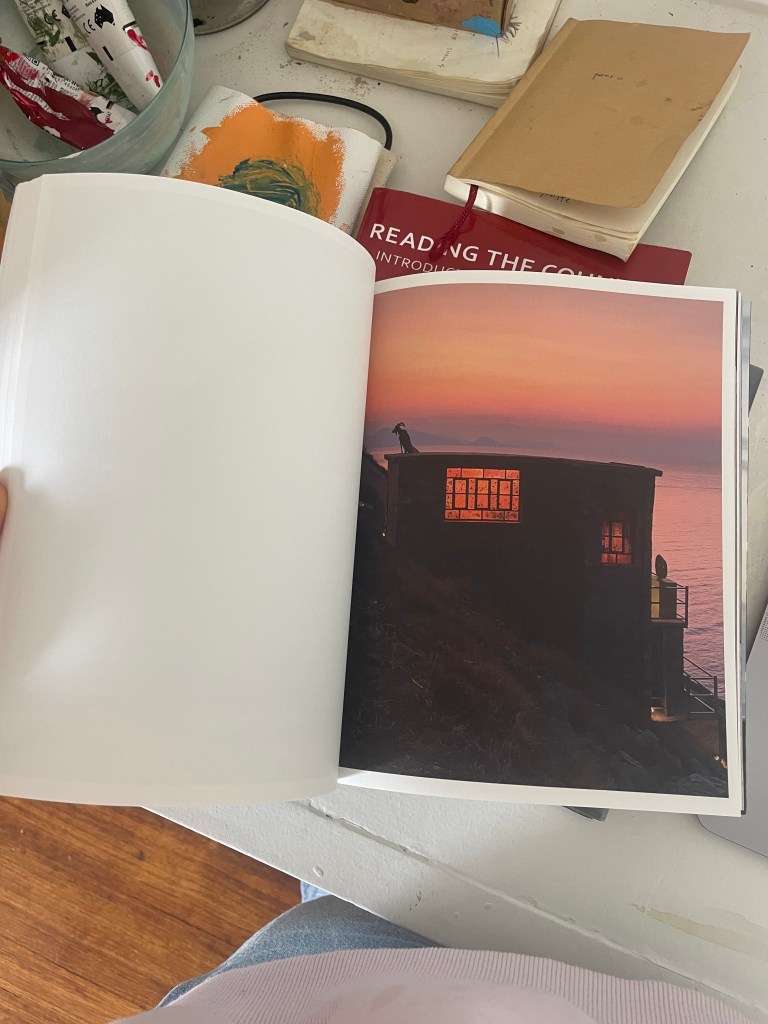

So the site for this show was the Slaughterhouse on Hydra, which remains pretty much unchanged, built into the side of the rocks opening onto the Aegean. The artist creates sculpture and plays with the space, like making rose tinted glass for windows that the sunlight bathes in and represents the blood that would have flowed into the sea from the animals.

All of this makes me thinks of a threshold, a border, in my own tiny history.

To visit my Dad every second weekend, when I was a kid, we passed the meat works and it was known because, as you reached it, down the southern end of town there was a grate in the road where to cows would get sent across and often we would have to wait in the car and watch them passing, heading from the left side, where they were living, to the right side, where they were about to die. And it was past this grate that, thirty minutes later, we would arrive at the sea on a friday evening as the sun was setting, creating that same pink in the sky from Kiki Smith’s stained glass. It’s the same colour as the elderberry tea I’m drinking right now, a light and somehow thick rose tint.

Artists notice things; artists are meant to notice things; associations are good to the artist because they are information the artist is noticing life. Surely to notice life is the only way to sense it; to access its memory?

‘Hydra’s slaughterhouse remains essentially unchanged. With three concrete stalls at its entrance and a simply constructed concrete room beyond, the space is both intimate and raw. Drains in the floor and hooks in the wall are remnants of days when goats or sheep would be quickly killed and strung up, their blood and entrails traversing a rough concrete pipe into the turquoise water below. From a small balcony hovering over the rocky shoreline, you might have seen the animals’ bright red insides dissolve into a wash of transparent purply-pink–at once repulsive and jarringly beautiful.’

It’s the same purply-pink the sky would go in Emu Park; the same kind of colour that I praise now in St Kilda–that Kikky Smith found in the stained glass. And I can’t help thinking about how happy those fish must have been, that lived below the slaughterhouse. It wasn’t so romantic in the town I grew up in, all that stuff went straight into bakery pie meat, which I ate, and made us strong fish.

‘The visceral and abject merging with the numinous and ever-changing: this blurred dissolution of the corporeal into a state of formlessness (and vice versa) is a theme Smith plays with endlessly in her work. The body–its anatomy, flesh, hair, sex, and soul–is the pivot from which her imagery originates and soars’

Let’s quickly break that quote down for the team at large – it is a big team, this team here us – because we don’t want to leave anyone out (which art often does and that certainly isn’t what makes us great) and we are trying to be great. Visceral means relating the the intellect of feelings and the nervous system, instinctive. I think maybe working from here makes great art? If we can find a good way to show it (I’ll try talk more to this nother time). Abject is something bad, like a slaughterhouse, or like a smelly groin – things we don’t want to see but maybe great artists make us see them. Corporeal means relating to the material body. So Kiki Smith makes these bad things into art; makes them formless like the light through the windows representing the blood from slaughtered animals that looks beautiful. She deals with the murky underworld of the soul so that you might have the chance to remember it.

So, what makes a great artist? It looks like I might have to keep pondering this question next week (and on unto infin?). Well at least last week we put a fork in the eyes that it might lie in fame or success (snooze town), which was nice to get out of the way quick – burn it down, shitty little thing that makes people lazy idiots who forget that the everyman is an artist and how lucky they are, and onto the much more interesting topic of slaughterhouse and memory. We don’t love to look at death or to enchant the idea of its beauty, which seems to be another job for the artist and perhaps what might make them a great one, like Kiki Smith.

What is visceral and abject to us now and how can we turn it into something beautiful to look at so that the viewer might re-see it beautifully? Like this st kilda sunset last night:

And just to be cute, before I go, riffing on Maggie’s Wright’s writing from earlier in this post: maybe art speaks to the collective memory of a us – of you, which, though relatively small, can be espied in the majestic and distant placement of stars? Maybe art, then, can save us from this hell?

p.s I bought my copy of Memory by Kiki Smith from Readings Carlton (it was expensive, but worth it).

Ciao for now 🙂

Oliver Shaw. 11: 13 AM. Mon 2 Sep.

Leave a comment